Federico Fellini would have directed the camera towards this last aspect: real, vulgar and ordinary, and I would say even more. Can you see that, over there in the background? Small, almost imperceptible, but it exists right next to the majestic building. A woman has emerged from the doorway of her house in a flowered apron, glasses, lilac-white hair and a dressing gown as if she doesn’t need to go out all day. She sits on the steps by the front door. She doesn’t seem to mind the other people in the square, she has accepted them as part of the everyday life of the neighbourhood. She texts, tries to call and, like my grandmother, she can’t quite figure out how to use the phone, so she calls a child for help. What child? The one who has been approaching me for a while without me noticing, I’m taking notes and he’s watching what I’m doing, he’s all over my notebook. Here, the line between the public and the private is very fine.

I return to the alleys of hanging clothes, in every direction I see bedsheets, towels, shirts, trousers, dresses, underwear and… flags! Blue and white, the colours of the Naples football team, the flags are to be found not only on the clotheslines but also on the balconies, terraces and walls. The streets are all dressed in the same palette and some are decorated with cardboard busts of the players, hung on wires from one window to the next, raised in the sky. “Grazie ragazzi!” The players are continually thanked on posters and murals. Thanks for what? This season SSC Napoli won the Italian league, a great victory that fans can’t help but celebrate, just like all the victories that Diego Armando Maradona brought from 1984 to 1992.

During the eighties and early nineties, the most popular neighbourhoods of Naples had a serious social problem, heroin. The futile and unfortunate death of many young people who succumbed to it and the economic recession that ravaged the country was compensated by Maradona’s one hundred and fifteen goals. The Neapolitans then deified him to the point of starring in the most prominent murals in the Quartieri Spagnoli and remaining in the imagination of children who kick the ball around the streets and staircases painted in the colours of the city’s team. Another reference in urban art to the Pibe de Oro is the mouth painted on some steps, representing Club Atlético Boca Junior, the Argentinian team where he scored thirty-five goals. The mouth, red and raging, in honour of the God; the cross at the top, sacred and solemn, represents the Passion of Christ.

Both deceased, the former passed away only three years ago, in 2020, and to find out how long ago the latter passed I only have to subtract thirty-three from the current year. Equally venerated despite the time difference, although here they are not the only ones, there are others who have died. The father, the son, but not the holy spirit, now I am referring to the grandmother, the uncle, the cousin… amen. To remember them there are no large murals, simply a niche with the figure of Jesus Christ crucified, the figure of San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples, and the photographs of deceased relatives. Absolute adoration for those on the other side of the glass, locked with a key that the head of the family carefully keeps for a monthly fee which he pays religiously. Christ, Maradona, football players, family members… And why not idolise comedians? Although he was born in Rione Sanità, Totò also has his memorial in the neighbourhood: a statue, elegant and pompous, so you think? It’s a mural. A paradigm of Italian neorealism, Totò has brought laughter and tears from spectators all over the world. Not all the deceased have the same merit, may he rest in peace.

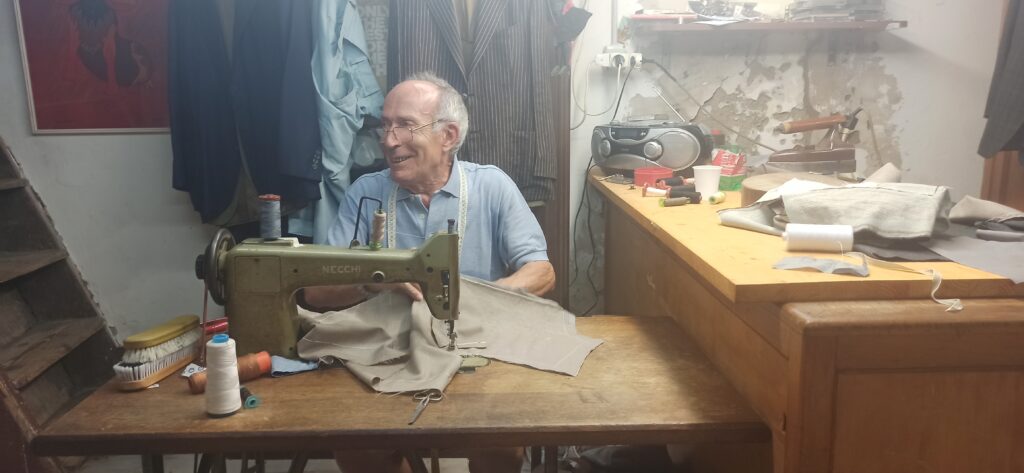

Giacomo has been in business for sixty-five years. He is a tailor, he has a small workshop where he makes all kinds of garments, suits and coats. Anything that would cost between ten or fifteen thousand euros in Paris, London or Barcelona, he sells for two thousand. Made-to-measure, personalised and according to your specifications. Some have asked him to sew the silhouette of a motorbike on the jacket as an emotional keepsake of the Quartieri Spagnoli. Motorbikes are part of the neighbourhood, it’s not just the neighbour’s son who has one by chance or because he needs it to go to university. The lady who leans on the ground floor doorway to chat has one too. The little girl next to her, her ten-year-old granddaughter, surely rides in front of her without a helmet, I’ve seen so many of those in Naples… even children riding on their own! I’ve already seen a few around here, as well as whole families on a single bike: the dad, the mum, the niece… I don’t know which is worse. Their photograph will end up in the niche and they will be venerated with the same passion with which they drive.

Dead or alive, the World Heritage of the Quartieri Spagnoli is in every entity, omnipresent on the big screen, gigantic murals, niches and in conversations at street level. The camera shot is left to the visitor’s choice, we observe the surroundings with the lenses and from the angle we decide, according to the style and context. A neighbourhood locked in the past, the decadence and the memories, and this is how we intend it to appear in every artistic expression, which is nothing more than preserving in a photograph, film or drawing something that should not be modified, and even more so, something that is revered as what it is now and not what will become. So come, photograph, and film; help to preserve.